Sally Mann The Naked and the Dead. Article by Blake Morrison, The Guardian 29th May 2010

Other Sally Mann posts here and hereSally Mann The Naked and the

Dead. Article by Blake Morrison, The Guardian 29th May 2010

From close-ups of rotting corpses to

those controversial portraits of her children baring all, Sally Mann has a gift

for provocation. Blake Morrison asks her why she likes 'pushing buttons'

Sally

Mann admits to being a little exasperated. Described by Time magazine in 2001 as "America's

best photographer", she is nothing if not adventurous, ranging widely in

subject matter and technique, but to most people she is known, if at all,

for just one thing: "Oh, she's the one who photographed her children

naked."

It's exasperating in several ways:

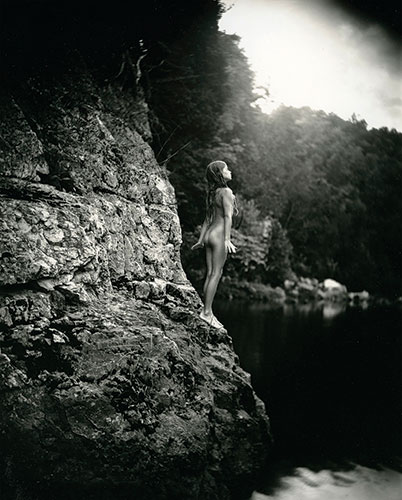

because the photographs in question - published in the book Immediate Family,

in 1992 - made her famous for the wrong reasons; because critics exaggerated

the intimacy of the photos at the expense of their artfulness; and because the

American religious right accused her of pornography when her camera was

capturing beauty and transience. "I've counted," Mann says. "Out

of the 65 photos in the book, only 13 show the children naked. There was no

internet in those days. I'd never seen child pornography. It wasn't in people's

consciousness. Showing my children's bodies didn't seem unusual to me.

Exploitation was the farthest thing from my mind."

In Britain,

perceptions of Mann are particularly skewed because she has never had a solo

exhibition here. That omission will be put right next month, at the Photographers' Gallery in London, with a

show representing different phases of a career that began in the 1970s. The

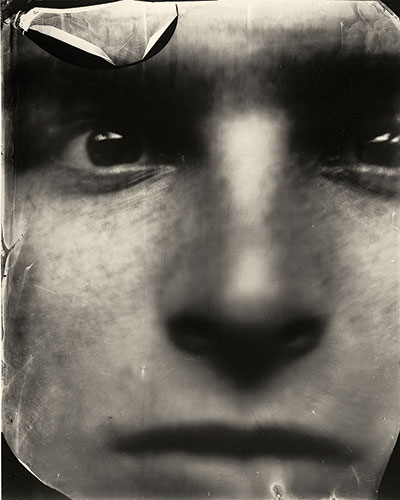

Immediate Family series is complemented by haunting studies of the grown-up

faces of her children, Emmet, Jessie and Virginia, all now in their 20s. Mann's

identity as a southern artist (she grew up near, and still lives among, the Blue Ridge

Mountains of Virginia) is expressed in a series of landscapes,

focusing on swamps and trees. Most challenging of all are her photographs of

decomposing bodies as they melt into and meld with the land.

Mann has a gift

for provoking strong reactions ("I like pushing buttons") and her

pictures of rotting corpses certainly do that. She took them at the University of

Tennessee's anthropological facility at Knoxville, aka the

"body farm", where human decomposition is studied scientifically. The

bodies are mostly left in an outdoor setting and lie there for months or even

years. In Steven Cantor's 2006 television

documentary about Mann, she is observed happily wandering from

cadaver to cadaver, prodding this body part and stroking that one, unfazed by

the maggots and reek of decay.

"Death makes

us sad, but it can also make us feel more alive," she says. "I

couldn't wait to get there. The smell didn't bother me. And you should see the

colours - they're really beautiful. As Wallace Stevens says,

death is the mother of beauty."

Mann called the

series What Remains, her point being that death is not an end, that nature goes

on doing its work long after the body has become a carapace. When her exhibition

of that title opened in Washington in 2004, most reviewers got the

point: "But not the woman in the New York Times, who freaked out and

called the photos gross." Mann was surprised to see an art critic using

the vocabulary of a 10-year-old, but not by the underlying prejudice:

"There's a new prudery around death. We've moved it into hospital,

behind screens, and no longer wear black markers to acknowledge its presence.

It's become unmentionable."

More remarkable

was the fact that no one questioned her right to publish the photos;

there had been endless sermonising about her portrayal of her children, but

this time there was none. "If there's any time when you're vulnerable,

it's when you're dead. In life, those people had pride and privacy. I felt

sorry for them. I thought if they knew I was taking photos, without them having

a chance to comb their hair or put their teeth in, they'd die of shame. So I expected

critics to ask: is this right?

"I was ready with my answer: all these people had signed release forms. I've done the same now, donated my body for research. But then I discovered that some of the corpses were street people who hadn't signed releases. And of course even those who did sign probably thought the photos would be scientific, not artsy-fartsy. So though I was given a free hand - 'Go on,' they said, when a fresh batch arrived, 'unzip the body bags and get them out' - I decided to keep the subjects anonymous. I didn't want to aestheticise them, either. It was important to treat them with respect."

There are various

sources for Mann's preoccupation with mortality. The shooting of an escaped

prisoner in the grounds of her farm in Lexington. The death of her greyhound,

Eva, whose bones - retrieved from the cage in which Mann had buried her - she

later photographed ("That was when I learned how efficient death is. After

14 months, the skeleton had been picked completely clean"). Or, years

before, the death of her father, for which she was present and which set her

wondering, "Where did all of that him-ness go?" Even the photographs

of her children are littered with memento mori: a dead deer in one, a dead

weasel in another.

In truth, though,

Mann's lively obsession with death - her capacity to be unsqueamish about it

while seeing its thumbprint everywhere - originated way back in early

childhood. Her father was a country doctor who had seen his share of death and

who liked to say there were only three subjects for art: sex, death and whimsy.

He was himself an artist in his spare time, and his whimsical creations

included a man with three penises (Portnoy's Triple Complaint) carved from a

tree trunk. It was an unconventional, rural childhood, middle class but

bohemian: no church, no country club, no television. Mann describes herself as

a "feral child", running naked with dogs or riding her horse with

only a string through its mouth.

She always knew

she would be an artist of some kind, and after marrying in her teens,

getting a good degree and studying creative writing, she settled on photography,

which she'd taken up while at school. The assignments were far from glamorous -

"The manager of Pizza Hut shaking hands with a prize college athlete: I

did that sort of thing for 10 years" - but she scraped a living from them

and nurtured more experimental work on the side. Then came an exhibition, a

book called Second Sight,

and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and National Endowment for the Arts. While raising

her three children in the 1980s, she worked to the principle that art is about

the ordinary and lies right under our noses. Her reputation was steadily

growing, but New York seemed a long way away ("It didn't help my career to

be living in Appalachia") and she remained comparatively unknown until

Immediate Family became a publishing sensation in 1992.

It's not a period

she likes to dwell on, but for a series of forthcoming lectures she has

forced herself to look back and ask the questions her critics have asked.

"Knowing what I now know, would I have taken the photos? Probably.

Would I have released them differently? Maybe. Do I regret them?

Absolutely not. I knew they were hard-hitting and that publishing them was

a gamble, but at another level I lived at a remove, in a state of naivety, and

the photos - many of them taken by the river where we spent vacations - seemed

perfectly natural. Had they destroyed my relationship with my children, it

would have been too high a price to pay. And, of course, I kept hearing

that the photos would screw them up once they were older. When they were going

through the usual bumps teenagers go through, I did sometimes wonder: is

this because of the pictures? But I don't think they were affected much at

all."

Mann has always

described these photos as a collaboration - Jessie, in particular, seems

to revel in the role of model, whether wearing a pearl necklace or brandishing

a candy cigarette. Signs of upset, injury and danger abound - a bloody nose, a

wet bed, a skin rash, an approaching (plastic?) alligator - but the children

came through OK and continue to pose for their mother.

The same goes for

her husband, Larry, who has been posing for Mann for more than 40 years:

"Larry has such confidence in my art," she says. "Far more

than I have." Working together on a series of studio nudes, Proud Flesh

(exhibited in the US last year), was, as she puts it, "a chance to spend

quiet afternoons together: no phone, no kids, two fingers of bourbon, the smell

of the ether, the two of us - still in love, still at work."

As well as these

abstract studies, which use the wet plate, or collodion, process and

make a virtue of the smears and distortions it can throw up, she has long been

compiling a much bigger series called Marital Trust, depicting Larry in a

variety of contexts - domestic, parental, sexual. Mann is well aware of how

radical these images are: the female artist gazing on the male model, rather

than vice versa. For now, though, she is holding them back: "This may

sound hubristic, but they're beautiful pictures, like nothing I've ever seen

before, and Larry looks terrific in them. But he's still working as a city

attorney and I don't want to embarrass him. Maybe after he's retired..."

For the moment,

she's at work on another project, about race. "It's a touchy subject, but

as a southerner you can't ignore our history any more than a Renaissance

painter can ignore the Virgin Mary. And it's impossible to drive down a road or

eat a vegetable or pass a church without being reminded of slavery." She

has previously explored the subject by photographing sites of civil war

battles, swamps through which slaves tried to escape their owners and the river

into which the body of the murdered black teenager Emmett Till was thrown in 1955 (a trigger

for the civil rights movement). Now she's taking portraits of men whose

ancestors were slaves.

Next year, Mann

will be 60, and she frets about becoming old news. The London exhibition is a worry,

too: if the current fashion is for coolness and cerebralism, will we Brits find

her too passionate, romantic, melancholy, sentimental? But the show has been a

success in Scandinavia. And there's the reassurance of knowing how many

photographs of Larry and the children she hasn't yet shown. "I think of it

as my aesthetic savings account - and I'm not talking about money. Whatever

fleeting discomfort I felt or caused while taking them, those photos are worth

much more. It's like having written Ulysses and put it under the bed. Forgive

me - that does sound hubristic."